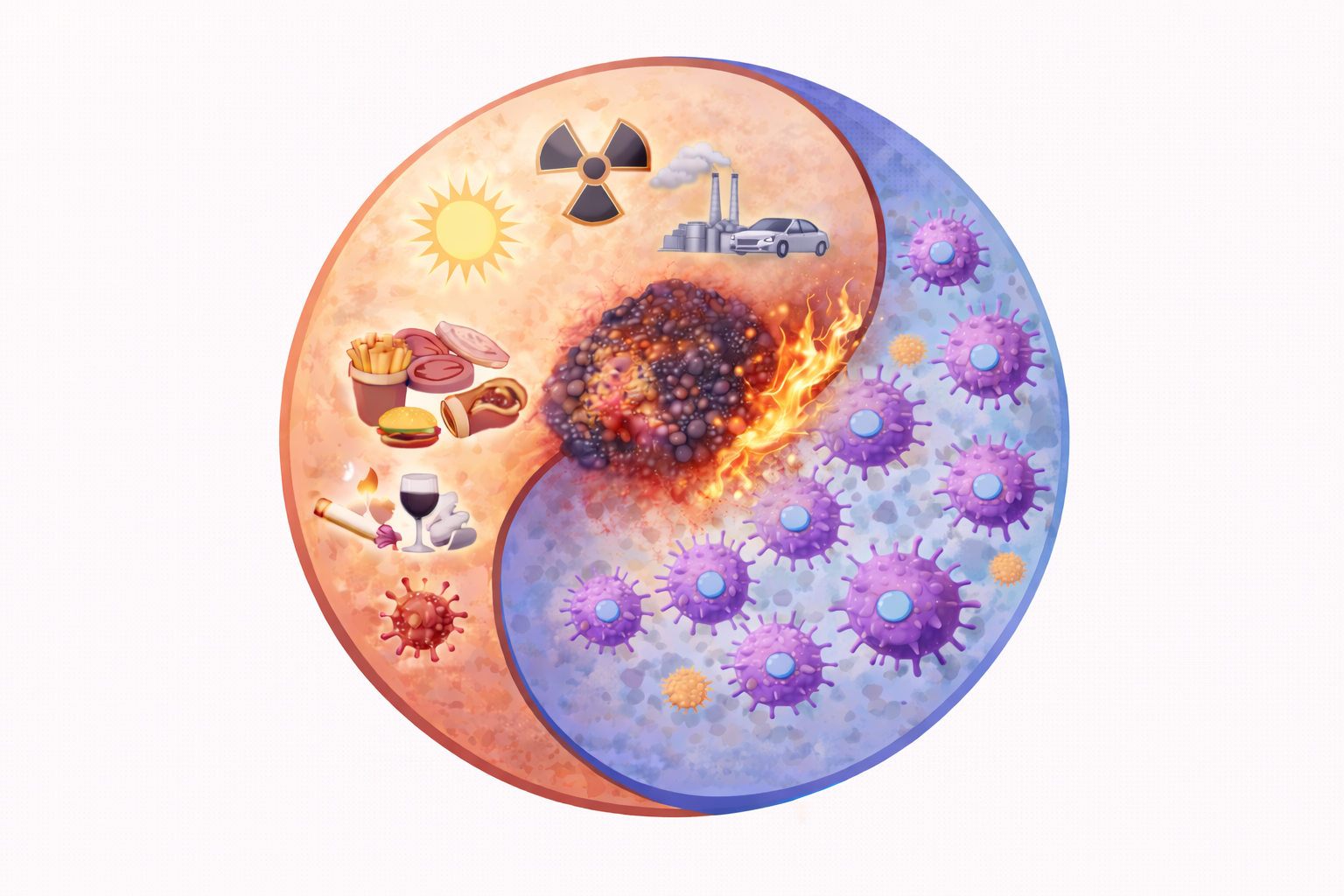

The study discovered that while cancer cells carry a vast array of mutations, not all of these mutations have the same impact on how tumors interact with the immune system. By analyzing nearly 9,300 cancer genomes across various cancer types, the researchers identified five dominant patterns of protein-altering mutations—called amino acid substitution signatures. These patterns help determine how visible a tumor is to the immune system.

When DNA is damaged by external factors like tobacco smoke or UV light, or by internal errors during replication, the mutations affect the building blocks of proteins (amino acids). Instead of a random mix of changes, nearly all tumors are dominated by one of five characteristic mutation patterns.

Crucially, these patterns do more than just serve as molecular fingerprints for how the mutations arose—they also influence how the immune system detects the tumor. Some patterns lead to the production of highly immunogenic protein fragments (neoantigens) that activate immune cells, while others create less recognizable neoantigens, resulting in „cold” tumors that avoid immune detection.

One key finding involves a mutation pattern linked to DNA repair defects and chemical exposures, which often results in poor responses to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies, despite having a high overall mutational burden. This suggests that a tumor can have many mutations and still generate too few effective immune targets.

The study also revealed that certain genetic variants in the human immune system, like specific HLA class I types common in Europeans, can partially counteract this effect, making mutated peptides more visible to T cells. This implies that the same tumor may be more or less immunologically visible in different patients.

Overall, the findings suggest a more refined framework for predicting immunotherapy responses, emphasizing that tumor visibility to the immune system is determined not only by the number of mutations but also by the protein-level patterns those mutations create. This supports a personalized approach to immunotherapy, integrating tumor genomics with the patient’s immune genetic background.

The study’s findings have broader implications for clinical practice, offering the potential to reduce unnecessary treatments, minimize side effects, and shorten the time needed to identify effective therapies for individual patients. The research was carried out through collaboration between multiple research groups and funded by international and national grants.