Gergő Mihály Balogh, Balázs Koncz, Leó Asztalos, Eszter Ari, Nikolett Gémes, Gábor J. Szebeni, Benjamin Tamás Papp, Franciska Tóth, Balázs Papp, Csaba Pál & Máté Manczinger

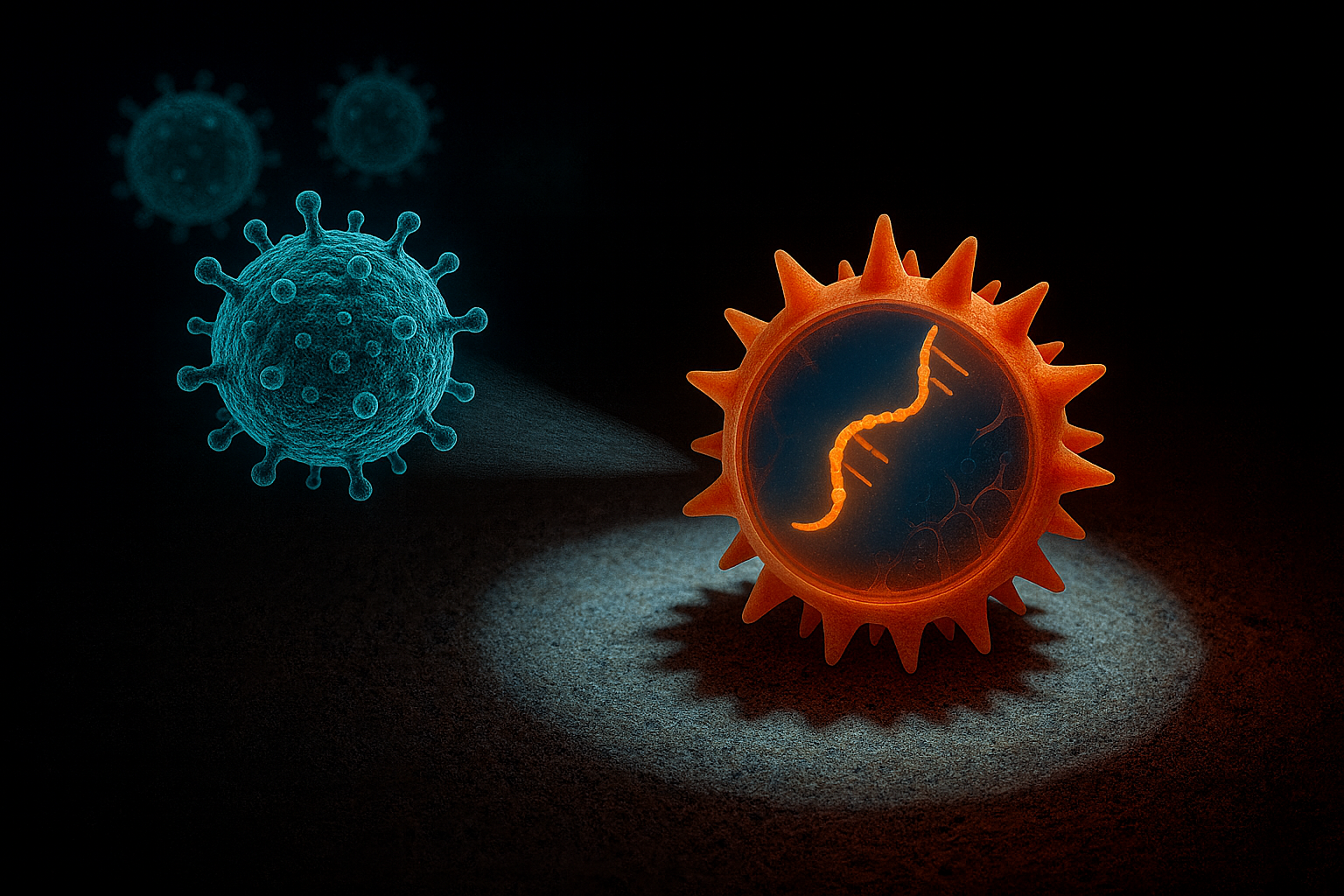

The eternal game between viruses and the immune system

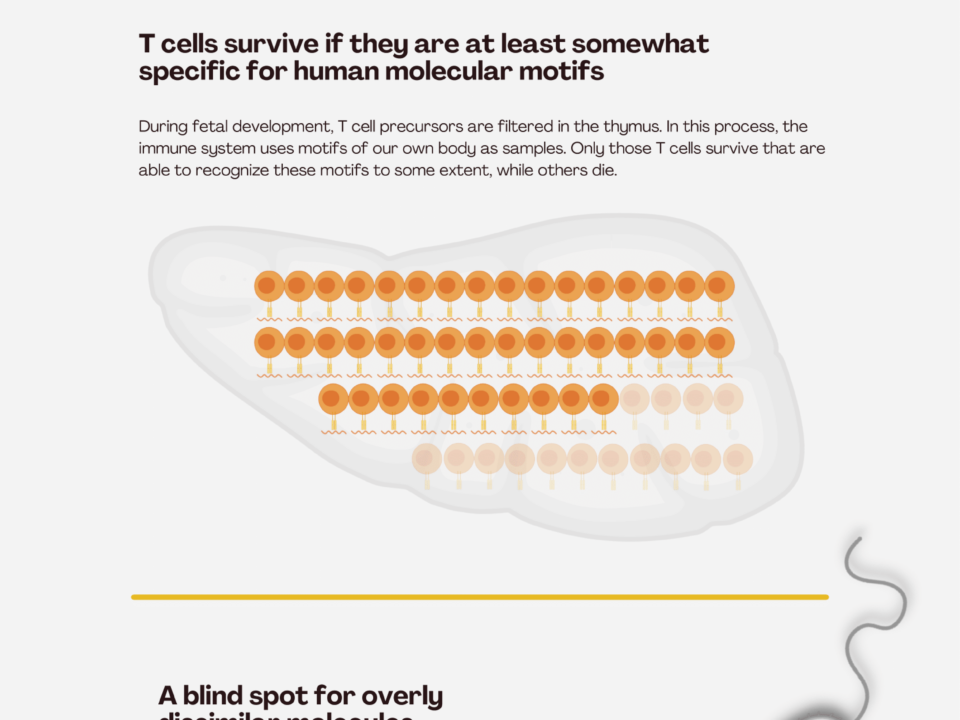

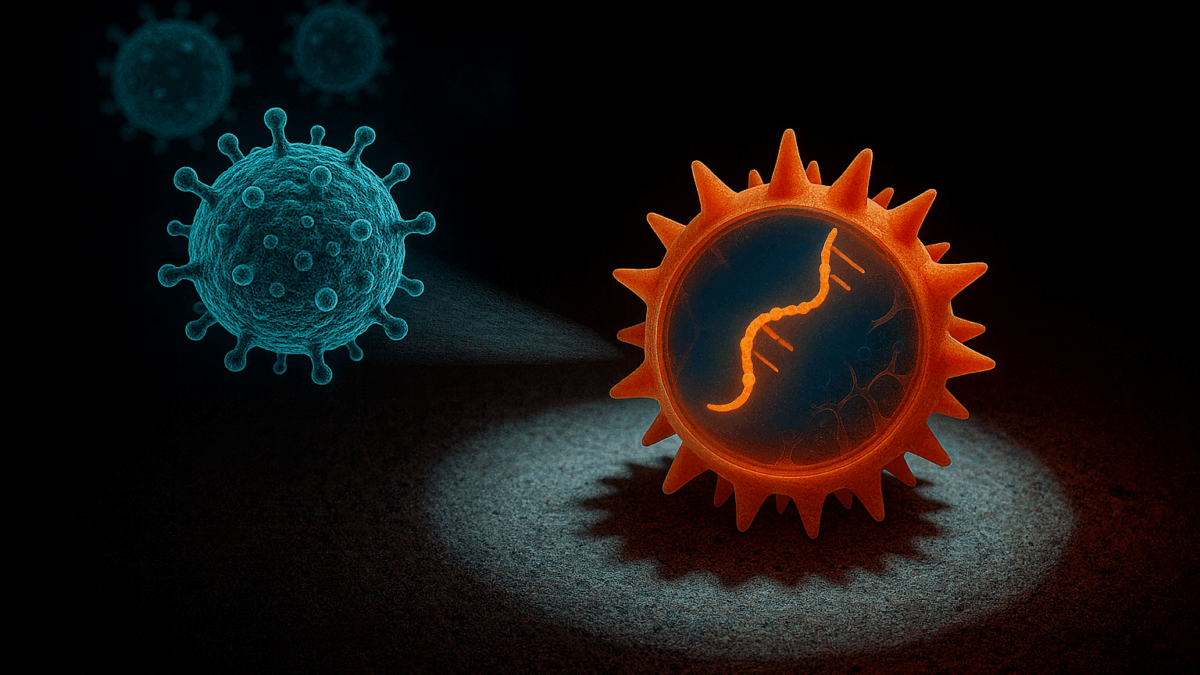

During viral infections, our immune system responds through multiple layers of defense. Following a rapid innate response, the adaptive immune system is activated, which can specifically recognize and eliminate infected cells. Central to this process are HLA-I (human leukocyte antigen class I) molecules—cell surface proteins that present small fragments of viral proteins (peptides) from within the cell to T cells of the immune system. Based on this information, T cells determine whether a cell is infected and, if so, destroy it.

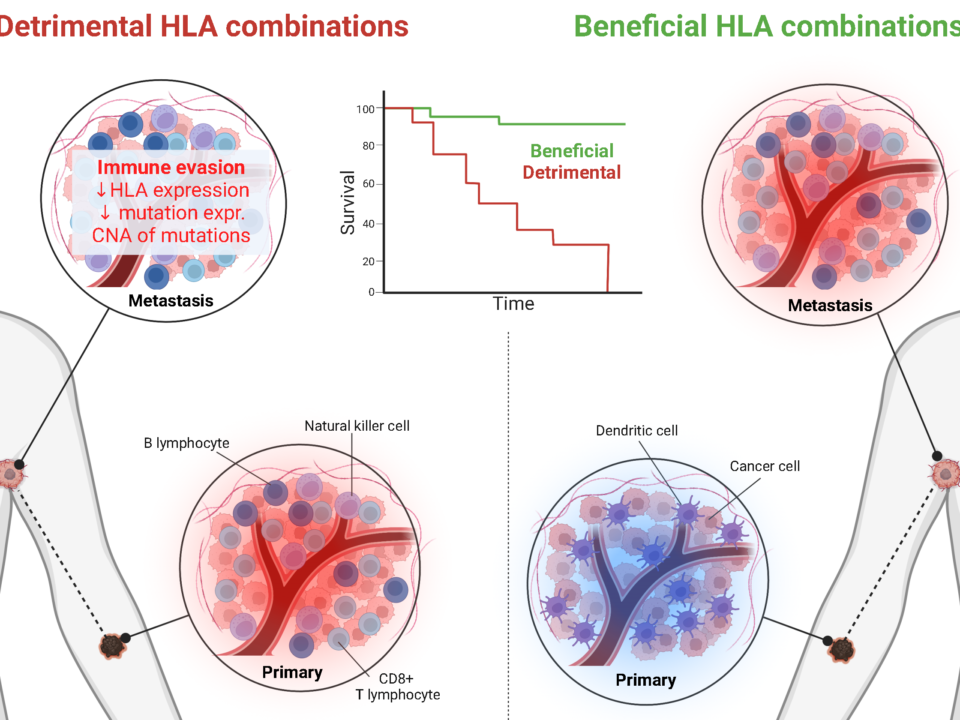

The HLA system is highly diverse: thousands of HLA-I variants exist in the human population, each capable of binding different peptide fragments. This genetic diversity influences which parts of a virus an individual’s immune system can detect, partially determining the severity of the disease.

Previous studies have shown that certain SARS-CoV-2 mutations help the virus evade immune detection, effectively becoming “invisible” to some HLA variants. However, the current study observed the opposite effect via a remarkable mechanism. By analyzing millions of viral sequences collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and cross-referencing with previous literature, researchers identified a clear pattern. A significant portion of SARS-CoV-2 mutations was not random but caused by a family of human enzymes called APOBEC3, which play an important role in antiviral defense. These enzymes chemically modify the virus’s genetic material, converting cytosine (C) to uracil (U), thereby altering viral proteins.

Evidence from data and clinical correlations

The researchers examined how these changes affect binding to HLA-I molecules, i.e., immune recognition. They found that in 99% of cases, C→U mutations increased the detectability of viral peptides by HLA-I. In other words, APOBEC3 activity generates viral fragments that the immune system can recognize more easily, enhancing the effectiveness of subsequent adaptive responses. The Szeged research team analyzed thousands of SARS-CoV-2 variants and experimentally confirmed that peptides altered by APOBEC3 bind more strongly to HLA-I molecules and trigger greater T cell activation compared to the original viral sequences.

These findings were further supported by a large dataset of over 17,000 COVID-19 patients in the UK. Individuals whose HLA-I types gained few new peptides from APOBEC3-induced mutations tended to experience more severe disease. This suggests that the interplay between HLA type and APOBEC3 activity can influence clinical outcomes.

A dialogue between immunity and evolution

The study also revealed geographic differences in APOBEC-induced mutations. HLA-I variants common in East and South Asia gained particularly many new peptides, consistent with the idea that past coronavirus outbreaks may have left genetic imprints on immune-related genes in these populations. This phenomenon is not unique to SARS-CoV-2. APOBEC3 activity has been documented in other viruses, such as HIV and variola (smallpox), suggesting a general defensive mechanism by which the immune system not only detects and eliminates pathogens but actively shapes their evolution.

Why this matters?

The research offers a new perspective on virus–host interactions. Viral mutations do not always serve the virus; in some cases, they assist the immune system. APOBEC3-induced mutational patterns could help predict which viral protein variants are likely to appear early in a pandemic, providing critical insight for vaccine development and personalized therapies.